Recently I have been re-reading some of my notes from my Computer Science degree, in which one particular second-year course immediately caught my attention. The course focused on, amongst other things, finite state machines and their role in theoretical computer science.

It got me thinking “Could I implement these in Kotlin and how might they be useful in the real world?”, a question I immediately felt I had to set out and answer. However, having graduated from university six years ago and with little exposure to ‘finite state machine’ or ‘automata’ theory since, there is a lot to cover before I can answer my question. At the very least I hope you learn something, I know I sure will.

To kick things off in this series of blogs, we will first need to reacquaint ourselves with what a finite state machine actually is.

Well, what are they?

Wikipedia defines a state machine, also known as automata, as being a ‘mathematical model of computation’. Sounds fancy but in layman’s terms, this just means any computation, that through a given a set of inputs, clearly defines how a set of outputs are reached. It can be thought of as an abstract concept of a ‘virtual machine’ in which commands are received, processed and then executed to give an expected output.

A finite state machine extends this definition by enforcing the virtual machine to be in a subset of known finite states at any given point.

Finite state automata come in flavours known as ‘deterministic’ or ‘nondeterministic’. These two variants differ through the maximum number of states the automaton can transition to after being given an input. For a ‘deterministic finite automata’ (DFA) this number is just one, meaning the automaton can only ever be in a single state at any given time, whilst the ‘nondeterministic finite automata’ (NFA) is permitted to be in one or more states at any given point. For now, we will stick to the far easier DFAs as we will look at the definition of NFAs in a future part of this series.

Without realizing it you will interact with real-world examples of state-machines all the time. For example, a traffic signal, a game of tic-tac-toe and a vending machine can all be thought of as finite state machines despite all three being used very differently from each other in reality.

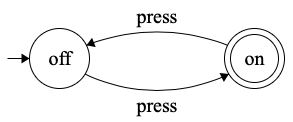

In its simplest form, a light switch can be thought of as a form of deterministic finite automaton too. Through each input (i.e. being pressed), the switch can transition back and forth between an ‘on’ state or ‘off’ state. This interaction can be represented visually by a simple transition diagram

A transition diagram for a light-switch

A transition diagram for a light-switch

To understand how we’d implement such a finite automaton in a programming language, we should first understand the mathematical definition of the DFA.

☕️ Please take a deep breath and grab some coffee because there’s some mathematics coming up. If you want to skip this part, feel free but I would recommend sticking with it for as long as you can! ☕️

Definition of DFAs

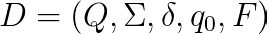

A deterministic finite automaton is defined mathematically by this quite scary looking ‘five-tuple’

Let’s break this down:

- D is our DFA we are defining

- Q is a finite set of states the automaton has; In our light switch example this would be { ‘on’, ‘off’ }

- Σ, the uppercase Greek letter sigma, is a finite set of input symbols; In our light switch example this would be { ‘press’ }

- δ, the Greek letter delta, is known as the ‘transition function’ and will be explained in depth momentarily.

- q0 is the initial starting state for the automaton. Let’s assume our lights start in the ‘off’ state.

- F is a set of final or ‘accepting’ states. In our example, because we don’t want to be left in the dark, let’s say having our lights ‘on’ is our accepting state.

Additionally, we also clarify three further rules for these definitions.

Firstly, we define the initial state q0 to be within the set of states the automata represents.

Next, we define the set of accepting states F is to be contained within, or equal to the set of states the automata represents Q.

Finally and arguably most importantly, we define δ the ‘transition function’ as a function that takes a state within the automata and an input symbol to produce the state for that given input.

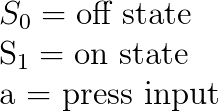

Confused? Let’s apply this definition for our light-switch example by first simplifying it. We shall rename our states and input to make the definition slightly more readable going forward.

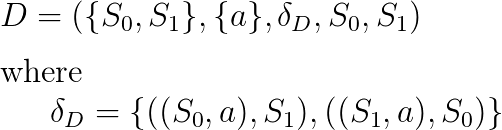

With these changes, we can formally define the light-switch DFA and its transition function δ using the definitions we looked at previously

The ‘transition’ function here looks slightly bizarre when written but itis simply defining that when S0, our initial state, is passed an input of ‘a’ it moves, or transitions, to S1, our accepting state. From there, it then moves back to S0 when given a further input of ‘a’ and thus we find ourselves back at the start, wondering who exactly is going to foot the huge electricity bill we have now presumably racked up!

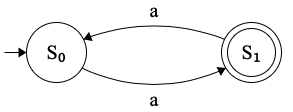

All of this is probably most understandable through the DFA being visually represented in our, now updated, state diagram for the light-switch.

A generalised transition diagram for a light-switch

A generalised transition diagram for a light-switch

The good news is, after all of that hard work, we have just formally defined our first DFA. The better news is it’s time to write some code!

Let’s do DFAs in Kotlin

If you stuck with the mathematics and didn’t skip to the ‘juicy part’ you may have noticed the definition of the DFA looked suspiciously like a class constructor 🤔

Applying what we learned within the formal definition, we can straight away create a rough DFA class with Kotlin

data class DFA(

val states: Set<State>,

val inputs: Set<Input>,

val delta: (State, Input) -> State,

val initialState: State,

val isFinalState: (State) -> Boolean

)This initial draft of our class is a super concise Kotlin data class. This implementation gives us the ability to test the equality of DFAs through the generated equals() method generated, for free, by the data class itself. The ‘transition function’ we previously defined formally is passed in the constructor as a function with the signature of (State, Input) -> State, meaning a function with two parameters of types State and Input that returns a State. This is all great, but these types have yet to be defined, so let’s do that now!

data class State(val name: String)

data class Input(val value: String)

val a = Input(“press”)

val s0 = State(“off”)

val s1 = State(“on”)Again, by using Kotlin’s data class we have easily created two classes that can be tested for equality and contain a reference to the name of the state. For now, these simple definitions are all we require to complete our model.

We now have all the components required to build a representation of the light-switch example as a DFAobject. For the sake of readability, I have added the named parameters to this DFA.

val dfa = DFA(

states = setOf(s0, s1),

inputs = setOf(a),

delta = { state: State, input: Input ->

when(input) {

a -> when (state) {

s0 -> s1

s1 -> s0

else -> state

}

else -> state

}

},

initialState = s0,

isFinalState = { state: State -> state == s1 }

)There are a few key points of interest here. Firstly, the DFA makes use of a lambda expression for the deltadefinition and handles the state transition for a given input by making it possible to call dfa.delta(state, input)elsewhere in future. Secondly, as the when calls are used as an expression, the elsebranches are mandatory as the compiler cannot prove in both instances that all the possible cases are covered. For a language that prides itself on pattern matching, this sucks.

Breaking the Seal

The good news is we can utilise Kotlin’s sealed classes to represent State and the restricted class hierarchy it follows. They can be thought of as an extension of enumerations and are fundamentally designed to be used when there are a very specific set of possible options. This means they can be applied with ease to our State model.

sealed class State

object S0 : State()

object S1 : State()In the above example, we can represent each of our states within our previously defined DFA as an object that inherits from the base State sealed class.

This gives us the fantastic ability to strip away the else in our when(state) { … }, as the compiler can now correctly infer what the expression requires to be exhaustive, meaning it is now able to provide a warning if one or more defined State objects are not handled within when expressions.

when (state) {

S0 -> S1

S1 -> S0

}🎉 Just like that, sealed classes have instantly made the code cleaner, super clever and much so easier to read!

Cool, so what’s next?

In the next parts of this series, we will look at defining and implementing the extended transition function known as ‘delta hat’ to start parsing DFAs and producing outputs.

We will also look at how we can create a non-deterministic finite automaton (NFA) and begin to use Kotlin to start generalising our definitions of NFAs and DFAs.

I hope you found this post interesting, please feel free to share your ideas and comments or tweet me with any feedback at @Sp4ghettiCode

Finally, don’t forget to like, share and let me know if you enjoyed this!

Extra Credit

If you want to skip ahead and read up on this area, I highly recommend the excellent Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation by John Hopcroft, Rajeev Motwani and Jeffrey Ullman.

In addition to this, the series was inspired by the G52MAL study guide written by my fellow alumni Dr Laurence E Day and Micheal B Gale that covers much of the broad subject of Machines and their Languages. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank both of them for their hard work and effort that they put into this guide, it was and continues to be a great source of help.